af Magazine

~The Asahi Glass Foundation’s web magazine on the global environment~

Restoring the Atmosphere by Reducing Methane Emissions: Hope, Health and Humanity

Methane--the second most emitted greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide (CO₂)--has about 90 times the global warming potential of CO₂. Yet, efforts to curb methane emissions have long lagged behind.

Professor Robert B. Jackson, one of the two laureates of the 2025 Blue Planet Prize, has been a leading advocate for cutting human-induced methane emissions as a means to restore a healthy carbon cycle.

"Reducing methane emissions has the most immediate benefits today for combatting climate change," says Professor Jackson.

In this interview, he discusses the carbon cycle, climate change, and why reducing methane offers one of our best hopes for restoring balance to the planet.

(Based on an interview conducted in May 2025 and his commemorative lecture in Tokyo on October 30, 2025.)

" The Carbon Cycle and Global Warming is Controlled Mainly by CO₂ and Methane"

"Climate change is already here. The year 2024 was the first year when the global average temperature exceeded pre-industrial levels by more than 1.5°C," Jackson began.

"We are already paying the price of climate change," he warned. "According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), billion-dollar weather disasters now occur eight times more frequently in the United States than several decades ago--costing an additional 100 billion dollars annually."

Since the 1990s, Jackson has analyzed carbon absorption and release in natural systems, conducting pioneering research on the carbon cycle※1. He has chaired the Global Carbon Project (GCP) since 2017, an international initiative that works with more than 1,000 scientists worldwide to collect, analyze, and publish data on the emission and absorption of greenhouse gases (GHGs).

"Earth's temperature is controlled by GHGs," Jackson explains. "Increased emissions of GHGs from human industrial and agricultural activities are driving climate change. Global CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels now total about 40 billion tons per year--a 60% increase since the 1990s. Even as awareness grows about the need for a decarbonized society and the use of renewable energy expands, CO₂ emissions continue to increase. Why is this happening?

"The main reason," Jackson notes, "is the continued growth in global energy demand. Renewable energy production is increasing, but there's little evidence that fossil fuel use has declined."

He stresses the need for multiple strategies: developing clean manufacturing technologies in sectors like steel and cement that are still far from decarbonization; improving energy efficiency (as many Japanese companies already do); and further expanding and utilizing renewable energy sources.

(Note 1) The carbon cycle refers to the process by which carbon moves and is exchanged in various forms among the Earth's atmosphere, biosphere, oceans, and geosphere. In natural ecosystems, absorption and release were originally balanced. However, since the Industrial Revolution, fossil fuel combustion and deforestation have upset this balance, raising atmospheric CO₂ levels and driving global warming.

Forests and Soils Absorb 30% of Global CO₂: The Hidden Power of Primary Forests

When. Jackson began studying the carbon cycle in the 1990s, scientists already knew that human-induced increases in GHGs were driving climate change. His focus turned to how rising CO₂ levels affect forests and grasslands--and, in turn, how these changes influence plant growth. Over the past three decades, his research has revealed that elevated CO₂ levels can boost plant growth by 10 to 20 percent.

"Forests absorb CO₂, which acts like a fertilizer that promotes growth," he explains. "In that sense, forests provide an invaluable service by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. But I've also learned that the soils, in which plants take root, are equally important. When healthy soils are lost through farming and deforestation, their ability to store organic carbon decreases. Carbon-rich soils retain more water and nutrients, so maintaining and restoring them is essential for the future of humanity."

Globally, forests and soils absorb about 30 percent of annual fossil CO₂ emissions. Jackson is now focusing on the extraordinary value of primary forests--ecosystems that have rarely been disturbed by humans. Working with other researchers, he is studying how these forests function, what ecological services they provide, and how their conservation can contribute to climate stability.

"With our Swedish colleagues, we studied several dozen primary forests and compared them with nearby commercial plantations under similar environmental conditions," Jackson says. "We wanted to see whether primary forests store more carbon and support a more diverse microbial community. We found that primary forests contain twice as much organic carbon in their soils and store 72 percent more total carbon overall compared to plantations."

Why is there such a difference in carbon storage between planted and primary forests? Jackson attributes the difference to two key factors.

"First, plantation methods affect the soil. Techniques such as mechanical trenching or mound planting can degrade soils, accelerating the loss of organic carbon. Second, the rich and diverse fungal communities found in primary forest soils may play a beneficial role. These fungi help improve soil health and fertility, increasing the soil's capacity to store carbon."

Building on these insights, Jackson and his team are now experimenting with transplanting beneficial fungi from primary forests into plantations. They hope this approach will enable commercial forests to store more carbon and help trees regrow.

"Healthy forest, including primary forests, and healthy soils provide many benefits, such as purifying air and water," Jackson concludes. "The two greatest changes that began a century ago, when GHGs started to increase, were the burning of fossil fuels and the clearing of forests. Protecting forests and soils is, without question, one of the most powerful ways to fight climate change today."

Reducing Methane: The Fastest Route to Climate Stability

Alongside carbon dioxide, Jackson emphasizes the urgent need to cut another GHG: methane (CH₄). He has been a global advocate for recognizing methane as the GHG that should be prioritized for immediate emission reductions.

"Methane has roughly 90 times the global warming potential of CO₂ over a 20-year period," he explains. "However, its atmospheric lifetime is only about 10 years, much shorter than that of other GHGs. This means that if we act now to reduce methane emissions, we can slow the rise in global average temperatures within the next two decades."

Because of its short lifetime, cutting methane has a powerful near-term impact on mitigating climate change. Yet, methane concentrations in the atmosphere are increasing even faster than those of carbon dioxide. Over the past five years, global methane emissions have surged rapidly, and atmospheric methane levels are now 2.6 times higher than pre-industrial levels. Jackson's recent work with the Global Carbon Project has shown that roughly two-thirds of global methane emissions come from human activities--agriculture, livestock, and energy infrastructure.

"Until recently, methane received relatively little attention among GHGs, particularly from anthropogenic sources," says Jackson. "Our research has mapped global methane emissions and identified key sources. Methane is well known to come from ruminant animals such as cows--through belching--and from the improper management of livestock manure. It also leaks from landfills and is released during oil and natural gas extraction. We've discovered that unintentional methane leaks are also a major problem. Methane escapes from extraction sites, pipelines, urban gas lines, and even household gas appliances--all adding up to major emissions."

Jackson's findings have had a significant influence on the development of international strategies and climate policies aimed at reducing methane emissions. Recognizing the importance of methane reduction, more than 100 countries-including the US, EU, and Japan-pledged in 2021 to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030, at the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow.

"However," he cautions, "this target is voluntary--it doesn't set binding commitments for individual countries. That's why it's critical that we continue to monitor and track methane emissions, both natural and human-induced, and identify where leaks are occurring. Only with accurate data and transparency can we reduce methane emissions worldwide."

To Save Our Planet and Protect Our Health and Lives

Jackson sees the energy sector as offering the most effective and cost-efficient opportunities to reduce methane emissions. He is currently engaged in a range of initiatives across this sector to detect and reduce methane leaks, including identifying emission "hotspots" using aircraft and helicopters, detecting leaks from city pipelines using mobile surveys, and directly measuring methane emissions from buildings and homes.

In Boston, for example, he and his colleagues identified more than 3,300 gas leaks in the city's pipeline system and traced many of them to aging cast-iron pipes. Their findings prompted swift action by both city and state governments, leading to the creation of the Massachusetts Natural Gas Pipeline Safety Code and the acceleration of pipeline replacement projects.

"This code created jobs, improved air quality, and reduced both greenhouse gas emissions and the risk of explosions," Jackson explains. "Ironically, the main driver of this change wasn't climate action--it was public safety."

As for what individuals can do, Jackson recommends replacing gas appliances with electric ones. Using clean electricity for cooking and heating not only reduces GHG emissions but also improves indoor air quality and personal health. In his commemorative lecture, Jackson announced that he would donate his prize money to Stanford University, which will match the amount to launch a new program, "Electrification for Health." The initiative aims to support low-income households worldwide, helping them reduce GHG emissions while improving health and indoor air quality.

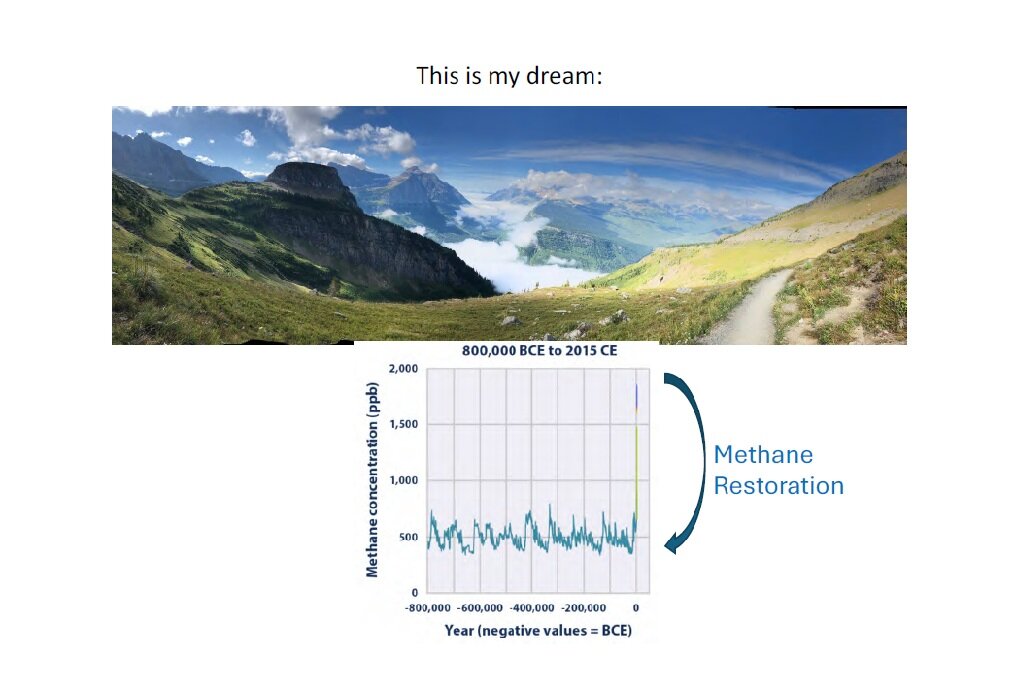

Professor Jackson calls his goal of stopping anthropogenic methane emissions and returning atmospheric levels to pre-industrial conditions within a few decades "restoring the atmosphere." To save our planet and protect our health and lives, he envisions science as a source of hope for humanity. His eyes, fixed on a future where the climate crisis is solved, clearly see a way forward.

"I believe we can stop climate change," Jackson says with conviction. "If we halt methane emissions and restore the atmosphere, we can mitigate global warming by 0.5°C. Lower methane levels would also reduce ground-level ozone concentrations and save hundreds of thousands of lives. Methane is the only GHG we can return to preindustrial levels in my lifetime. I want to witness that moment with my eyes."

Profile

Professor Robert B. Jackson

Department of Earth System Science, Stanford University

2025 Blue Planet Laureate

A leading authority on the carbon cycle in terrestrial ecosystems, Professor Jackson has conducted extensive research on how rising atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations affect forests and soils. His pioneering work has also quantified the global balance of GHGs--including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide--emitted from both fossil fuel use and natural ecosystems. Since 2017, he has served as Chair of the Global Carbon Project (GCP), an international initiative dedicated to monitoring and reducing GHG emissions worldwide. His 2024 book, Into the Clear Blue Sky (Scribner and Penguin Random House), was selected by The Times as one of the Top Science Books of 2024. In addition to his scientific work, Professor Jackson is also an accomplished poet and photographer, with his creative works featured in numerous media outlets.