Declining biodiversity: We must change our agricultural practices and eating habits to halt the extinction crisis --An interview with 2020 laureate Professor David Tilman on the importance of a plant-based diet--

"Plant-based" is a term used to describe food made from plants. We started to hear the word frequently in the last few years, but not many people can really explain why plant-based diet is gaining so much attention today. Professor David Tilman, one of the 2020 Blue Planet Prize laureates, focused on the concept of "eating habits" as a highly feasible solution to change our agricultural practices, which has a major impact on the natural environment, as well as to protect biodiversity. He scientifically proved that a plant-based diet is beneficial for both human health and the global environment. (Interviewed on May 18, 2022)

All species are specialists, coexisting on the earth by trading off their traits

Professor Tilman was born and raised on the shore of Lake Michigan in the United States, one of the world's five largest lakes. He spent his childhood in a rich natural environment, where he enjoyed chasing insects and observing flowers and frogs more than anything else. Eventually, he enrolled at the University of Michigan, where he came across the study of ecology and began to search for answers to a question: Why are there so many kinds of life on earth? How can they coexist?

"There are more than 5,000 species of mammals, more than 10,000 species of birds, and more than 300,000 species of plants. And when it comes to insects, we don't know how many. It is truly a wonderful and amazing fact that the earth is inhabited with such diverse organisms. When I was in my doctoral program, comments from a professor triggered my interest in two unexplained mysteries about biodiversity.

In the process of evolution, new species often compete with existing species and surprisingly they consistently coexisted with them. Why? That was the first question. The second question was what conditions are required for competing species of organisms to coexist with each other."

Professor Tilman then discovered that competing species achieve coexistence when inevitable tradeoffs occur. When species strengthen one of their abilities in the course of evolution, they must give up a different ability. In other words, species must pay some price to acquire a beneficial new trait. "All life on earth is constrained by these inevitable tradeoffs," Professor Tilman says.

"In human society, everyone is a specialist of some kind, such as a university professor, a lawyer, an engineer, or a mechanic. In the same manner, each species in nature is a talented specialist. These tradeoffs also help explain why life on earth became so diverse."

Biodiversity increases productivity. His research develops into exploring sustainable agriculture.

Within the community of ecologists in the 1970's and 1980's, the reason for the coexistence of many competing species was an unsolved mystery, as was the how the earth came to be so biologically diverse, The idea that "biodiversity," which is now undoubtedly valued, had a positive impact on the functioning of ecosystems was also not accepted by most ecologists during this era. Professor Tilman, anticipating that his ideas would stir up controversy in the world of ecological studies, decided that he would need rigorous field experiments to test his ideas about coexistence and biodiversity.

In 1988, when a serious drought hit the middle of the United States, he made a discovery. He found that the productivity of grassland vegetation was more resistant to drought and was recovering more quickly in the areas inhabited with many different plant species. Professor Tilman created a new experimental "farm" and started observation. He divided a large field into 160 plots and planted 18 different perennial grassland plant species in various randomly chosen combinations. Each plot contained either one species, or two species, or four species, or 8 species or 16 species. There were about 30 plots for each level of plant diversity.

"Every year, we cut and dry the plants in each plot to measure their mass. In our experiment, the total plant mass eventually became about 200% larger in plots where 16 species of plants coexisted than in the monocultural plots of these same species. That is, the productivity became 200% higher. We also found that as more time passed, the advantage of diversity increased. When compared with monocultural plots, the productivity of the 16-species plots was about 70% greater in the first several years. After about 20 years, it has been 200 to 250% greater," says Professor Tilman.

The "tradeoffs," or specializations, of each species were the cause of this greater productivity. Some species grow well in spring when temperatures are cool, other species grow best when temperatures are hot in the summer. Some species have deep roots, others have shallow roots. Some can grow well even on soils with low amounts of nitrogen. Other species can grow well when soils have low calcium, and others when potassium is low. Each species does something uniquely well, producing biomass in a way that no other species can. These different traits cause the total productivity of a diverse community of species to be much greater than can ever be produced by a less diverse community. Furthermore, it has recently been discovered that these differences in traits also have a long-term impact on soils. When there was greater plant diversity, the soil became more fertile through time, which also contributed to the improved productivity.

In human society, it has long been thought that cultivating a single crop, which is an agricultural monoculture, was the best way to have high agricultural productivity. In the 1960's the Green Revolution showed that grain production greatly increased with the use of chemical fertilizers. However, fertilization caused water and air pollution. Thinking that there must be an environment-friendly farming method that ensures the harvest of the crops needed, Professor Tilman worked with other researchers to highlight two ways to achieve sustainable agriculture.

The first is intercropping, or mixed cropping. It uses crop biodiversity to increase food production. When a good combination of two different crops was grown on every other ridge in a plot, productivity was greater than when the two crops were grown in monoculture. The other is to grow the right crops for an area with the right amount of fertilizer. In a grain farming region in China, for example, even when fertilizer application was reduced by 15%, the same amount of grain was harvested because farmers were told exactly how much fertilizer their crop required for their climate and their soil.

"Farmers can save money by buying only the amount of fertilizers they need, and this also causes water pollution and greenhouse gas emissions to be greatly reduced. For this approach to sustainable agriculture to spread throughout the world, it will be necessary to create a system in which scientifically rigorous advice is provided to farmers. This system could also help increase food production on the existing croplands of low-income countries, which would slow land clearing and help protect their biodiversity. This system should be a global priority."

For more than 20 years the EU has used this kind of detailed knowledge to regulate fertilizer use by farmers, allowing them to get higher yields while using less fertilizer and causing less pollution. A similar approach is being explored by China. However, there is no such policy in the United States or in most other countries. Global progress is slow. "We know how to solve this problem. It is time to do it and greatly reduce both pollution and species extinctions," emphasized Professor Tilman.

What is a diet that is good for health and beneficial for the environment? Traditional Japanese diet is a perfect example.

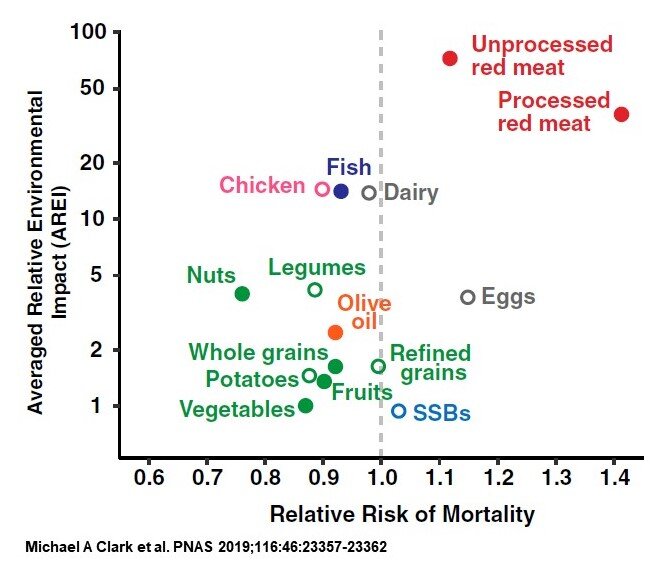

Along with sustainable agriculture, Professor Tilman paid close attention to the links between three elements: our eating habits, health, and the environment. Because our food choices affect health and what farmers grow, our diets also impact the environment. He named the situation, in which these three factors are intertwined, the "diet-health-environment trilemma." The first question he had was whether it was possible to solve this trilemma and create a win-win relationship. Collaborating with scientists from other fields and analyzing a huge amount of data, they found that eating healthy food also has a positive impact on the environment.

"Our discovery was not unexpected but it was highly encouraging. If we properly communicate this information, it may change people's eating habits. We found a great potential for solving both health and environmental problems," says Professor Tilman.

A healthy, environment-friendly diet is one that is centered on vegetables and fruits, unrefined whole grains, nuts and fish. Today, these eating habits are also called a "plant-based diet." The traditional Japanese diet fits this exactly. Other plant-based diets include a Mediterranean diet centered on unrefined grains, vegetables and seafood, and a traditional Indian vegetarian diet. Contrarily, the most serious problem for health and the environment is beef. Cattle farming requires the largest areas of farmland for raising the animals and cultivating their feed. Eating large amounts of red meats and processed red meats is very unhealthy. Production efficiency is poor, and the animals emit methane, a potent greenhouse gas, when they burp. Still, Professor Tilman does not think that it is necessarily wrong to eat a small amount of meat.

"Vitamin B12 occurs in seafood and red meat, and is a vitally important nutrient, especially for children. I think it's better to take a plant-based diet as 'more plants' and 'much less meat.' It doesn't have to mean eating no meat. Rather, it means that eating more unrefined grains, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and fish is good for your health and the environment. As a result of this diet, we can live longer, reduce illness, and maintain a healthier environment, achieving a win-win situation," says Professor Tilman. The finding of this study also attracted the attention of major food companies. Professor Tilman has had opportunities to directly talk with the heads of some companies. He says that the cautiously enthusiastic attitudes of the leaders suggests that a plant-based diet can become a global trend.

Correct knowledge and understanding of "plant-based diet" is important. "Delicious!" is key to scale-up

As Professor Tilman expected, sandwiches and hamburgers labeled "plant-based" started to appear on the menus of major coffee chains, hamburger chains, and other restaurants in Japan in the past few years. While appreciating these changes, he also warns that consumers need to have the right knowledge.

"If done properly, plant-based diets can have a positive influence on the environment and human health. However, for example, if you have a lot of sugar or cornstarch, or if you only have refined grains, it is not good for your health. Crops that use excessive chemical fertilizers are not the best choice for the environment, even if they do not affect human health. All of these issues need to be dealt with before foods are delivered to consumers. One way to do this is to certify and label products that are beneficial for the environment and health. One of my former students, Dr. Michael Clark, is working on this issue."

Professor Tilman emphasizes that in order to make big changes by spreading the right knowledge and proper eating habits, it is important to deliver an exciting experience.

"That is, offering delicious food. Using the creativity of cooks all over the world will be essential for changing our diets to be more plant-based. Chefs can create delicious new dishes with no meat, update traditional menus to modern styles, and so on. My dream is to produce a new popular TV cooking show where chefs compete with each other but only use ingredients that are good for both health and the environment. The champion is ultimately chosen for the tastiness of the dish. The viewers of the TV show would be excited to try the delicious new dishes, as would chefs in restaurants, and major food companies. I will be happy if someone who reads this column produces such a program," said Professor Tilman.

"There are two things we can do. To change our own behaviors and to influence the behaviors of others."

Professor Tilman is currently studying how to prevent large-scale extinction of organisms. It is a common understanding among ecologists that if nothing is done, large-scale extinctions will occur. He says it is important to stop land development for agriculture and livestock farming in the tropics. And this development is being fueled by a global trend in which higher income gives rise to higher red meat consumption. Even in these tough times, Professor Tilman never gives up his hope and keeps smiling to express his optimism. In May 2022, Professor Tilman participated in an online meeting with the Japanese youth, who are working on a project (Youth Environmental Advocacy), one of the events in commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the establishment of the Blue Planet Prize. In the meeting, Professor Tilman repeatedly encouraged the young people to stay hopeful.

"Good changes are happening, and the problems the earth is facing now will certainly be solved. Today's young people will become leaders in various fields in 20 to 40 years. In the business arena, for example, leading companies in 2050 will be those that are capable of developing products that support environmental conservation. I hope each of you will help solve environmental problems in your future role," said Professor Tilman to the participants.

Currently eight billion people live on earth. Thinking that we can only do small things to solve environmental problems, we tend to stop doing them. But Professor Tilman says positively, "There are things that anyone can do."

"Learn what is good for the environment and change your behavior, and you will then also influence the behaviors of others. If you are a schoolteacher, you can talk about environmental issues in the classroom. If you work in the field of communication, such as the media or SNS, you can write articles to have an impact. If you work in a company, you might be able to tell the story to your colleagues or clients. Listen carefully to what other people say and share your thoughts patiently. No change will happen overnight. We need to work on it gradually and constantly through our lifetimes," Professor Tilman says.

The tradeoff between species is true for humans as well. Each of us exists as a specialist, and there are things that each of us does best. We can use those skills to help improve the world. Professor Tilman's powerful message is encouraging all of us living today, illuminating the way to a sustainable future.

Profile

Professor David Tilman

Professor and Presidential Chair, University of Minnesota

Distinguished Professor, University of California, Santa Barbara

He has studied health and environmental impacts of agriculture and of dietary choices and demonstrated that while plant-based foods are beneficial to human health and the environment, red meats negatively affect both human health and the environment. Recognizing the tightly-linked diet-health-environment trilemma as a global challenge, he has advocated shifts towards diets and agricultural practices that are better for human health and the global environment. He was awarded the 2020 Blue Planet Prize.